Review: 'The Bees', by Laline Paull

The man stared through the trees, not listening.

"There – thought for a moment it had vanished."

An old wooden beehive stood camouflaged against the trees. The woman drew back.

"I won’t come any closer," she said. "I’m a bit funny about insects." (p. 1)

The reader knows from the beginning that the orchard hive is on an old, out-of-business farm being sold, to be demolished so its land can be added to a light-industrial complex. But the bees in the old wooden beehive don’t know it.

Bees are controlled so much by instinct that it is very difficult to realistically anthropomorphize them. But it has been done, in A Hive for the Honeybee by Soinbhe Lally (original Irish edition, February 1996; U.S. edition, March 1999), and the award-winning 1998-1999 five-issue comic book Clan Apis by Dr. Jay Hosler, a neurobiologist specializing in the study of honeybees, collected into a 158-page graphic novel in January 2000. And now there is Laline Paull’s complex dystopian The Bees.

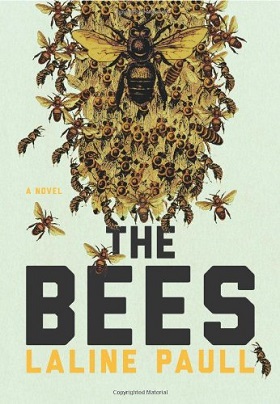

Front., bee illustrations from Meyers Konversations-Lexikon 1897, NYC, HarperCollinsPress/Ecco, May 2014, hardcover $25.99 (340 pages), Kindle $12.74.

Flora 717 has just been born, in a shabby Arrivals Hall meant for the hive’s lower-class workers:

Row upon row of cells like hers stretched into the distance, and there the cells were quiet but resonant, as if the occupants still slept. Immediately around her was great activity, with many recently broken and cleared-out chambers and many more cracking and falling as new bees arrived. The differing scents of her neighbors also came into focus, some sweeter, some sharper, all of them pleasant to absorb.

With a hard, erratic pulse in the ground, a young female came running down the corridor between the cells, her face frantic.

"Halt!" Harsh voices reverberated from both ends of the corridor and a strong astringent scent rose in the air. Every bee stopped moving except the young female, who stumbled and fell across Flora’s pile of debris. Then she clawed her way into the remains of the broken cell and huddled in the corner, her little hands up.

Cloaked in a bitter scent that hid their faces and made them identical, dark figures strode down the corridor toward Flora. Pushing her aside, they dragged out the weeping young bee. At the sight of their spiked gauntlets, a spasm of fear in Flora’s brain released more knowledge. They were police.

"You fled inspection." One of them pulled at the girl’s wings so another could examine the four still-wet membranes. The edge of one was shriveled.

"Spare me," she cried. "I will not fly; I will serve in any other way -"

"Deformity is evil. Deformity is not permitted."

Before the young bee could speak the two officers pressed her head down until there was a sharp crack. She hung limp between them and they dropped her body in the corridor.

"You." Their peculiar rasping voice addressed Flora. She did not know which one spoke, so she stared at the black hooks on the backs of their legs. "Hold still." Long black calipers slid from their gauntlets and they measured her height. "Excessive variation. Abnormal."

"That will be all, officers." At the kind voice and fragrant smell, the police released Flora. They bowed to a tall and well-groomed bee with a beautiful face.

"Sister Sage. This one is obscenely ugly."

"And excessively large-"

"It would appear so. Thank you officers, you may go."

Sister Sage waited for them to leave. She smiled at Flora. (pgs. 4-5)

Although the bees do not know that their hive is in danger from humans, they are aware of other, natural threats:

"Come, Sister. Unburden yourself." Sister Sage was calm and kind, and Sister Teasel dared look up.

"They say the season is deformed by rain, that the flowers shun us and fall unborn, that foragers are falling from the air and no one knows why!" She plucked at her fur convulsively. "They say we will starve and the babies will all die, and my little nurses are worrying so much I fear they will forget -" She shook her head. "Not that they do, Sister, ever, for they are most strictly supervised, and the rotas are always guarded even if they could count – you may kill me if it is not so." (p. 15)

Every bee in the hive has its place and its occupation from birth. “Accept, Obey, and Serve” is their mantra. The bees accept this without thinking, and the hive’s police ruthlessly kill any who deviate from the norm physically or mentally. Flora 717, born to be a lowly sanitation worker, is one of those deviates; but before the police can weed her out, she is taken under the protection of Sister Sage, a high-ranking member of the hive’s Melissae priestesshood. (In pre-Christian Greece, one of the goddess Aphrodite’s attributes was Melissa, the Queen bee, and her priestesses were called the Melissae. The Bees contains references to more than just the scientific study of bees.)

Sister Sage excuses her defense of Flora 717 by saying that she needs her for an experiment. Due to the bees’ unquestioning obedience, she is never asked to explain. Flora’s differences include the ability to wonder and question beyond a sanitation worker’s usual duties. These are usually forbidden, but Sister Sage recognizes that her ability to learn, plus her courage and strength, are assets that the hive needs during this unusually cold and damp summer, so she is permitted to survive. When the experiment is ended, Flora is still protected by Sister Sage’s sponsorship. She begins to live her own life, and to take on different roles within the hive:

With the release of the burden Flora shot up into the sunshine and flew loops of pure joy and relief. Her vision sharpened so that far below she could see two raucous bluebottles chase each other, and below them, small male mosquitos whined their song over a pond, their blue streamers fluttering from their antennae. Even lower, the dark, blood-filled females cruised at the water’s edge. Flora stored every minute detail before she surged higher. For the first time in her life she was utterly free, with no walls or rules to curb her, and she dived and soared for joy. The more the sun warmed her, the greater grew her strength and skill, and she looked for Lily 500 to thank her – but the old forager was already a speck in the distance. (p. 57)

She performs valuable services for the hive:

At the thought of the Queen, Flora scented the precious molecules of her divine fragrance, poised and spinning like jewels where the air currents converged. Her heart filled with passion and confidence, but as the hive came nearer and the earth and trees raced past below, she saw foragers streaming past through the orchard, racing for the landing board. A new scent mixed with the homecoming scent, and as Flora began her descent her venom sac swelled hard in her belly and her dagger unsheathed. The code was alarm, and the hive was under attack. (p. 58)

But there is one difference that cannot be permitted. When Flora feels the urge to produce fertile eggs after her meeting with the hive’s drones, breaking the commandment that only the Queen may bring future life to the hive, she knows that she must lay them and mix them in with the royal brood in secrecy lest she be torn apart. This becomes harder and harder as her larvae are discovered.

The Bees mixes episodes of Flora’s adventures outside the hive – escaping from bee-eating crows, attacks by vicious wasps, a deadly hailstorm, the dangers of a nearby human city, the theft of their honey by a human beekeeper – with her surreptitious laying of her forbidden eggs:

A wave of masking scent rolled into the Fanning Hall at the arrival of a police squad. Every sister working there looked up in disapproval, for despite the vigorous activity it was still a sacred place. Flora recognized the particularly harsh scent of Sister Inspector and watched her speaking quietly with Sister Sage. Very slowly she averted her antennae, lest her notice rouse their attention. The priestess turned.

"Immediately upon completion of repairs," Sister Sage announced, "the Treasury will be reconsecrated." She scanned the workers. "But the theft of our wealth has revealed a greater evil. We are no longer in any doubt: a laying worker hides among us. From now on there will be spot checks throughout the hive, day and night. Any sister who resists an officer will be deemed guilty. Is that clear?" (p. 184)

Flora’s personal championship of her child becomes submerged within the apocalyptic chaos of the death of the old Queen, the ritual fight for supremacy of two princesses to become the new Queen, a civil war between two worker castes, and more. The Bees is an anthropomorphic fantasy based on realistic bee behavior, and, as is well-known, realistic nature ain’t pretty. Find out for yourself whether there is a happy ending or not.

Ecco is today an imprint of publishing giant HarperCollinsPress. It was founded in 1971 as Ecco Press by Daniel Halpern as an independent publishing company. HCP acquired it in 1999, with Halpern continuing as its editor. The cover and frontispiece of “The Bees” are illustrations from 19th-century books on beekeeping.

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

The man stared through the trees, not listening.

The man stared through the trees, not listening.

Comments

Post new comment