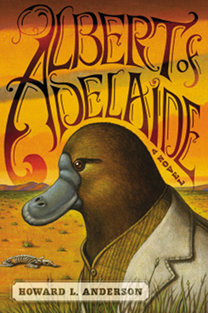

Review: 'Albert of Adelaide', by Howard L. Anderson

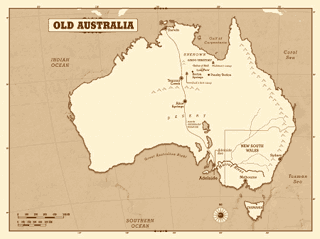

Australia today is not what it used to be. Civilization has settled into the southeast of the country, roughly from Adelaide to Sydney. Imported animals like sheep, foxes, and rabbits have replaced the older native animals. Kangaroos and wallabies are tolerated as “cute”, but other native animals have been relegated to zoos where they are penned in and stared at by humans. But there is a legend that somewhere in Australia, far from the human-settled southeast, isolated in the vast desert, there is a place where things haven’t changed and the original animal inhabitants live freely.

Australia today is not what it used to be. Civilization has settled into the southeast of the country, roughly from Adelaide to Sydney. Imported animals like sheep, foxes, and rabbits have replaced the older native animals. Kangaroos and wallabies are tolerated as “cute”, but other native animals have been relegated to zoos where they are penned in and stared at by humans. But there is a legend that somewhere in Australia, far from the human-settled southeast, isolated in the vast desert, there is a place where things haven’t changed and the original animal inhabitants live freely.

In the early morning of a day long after the war, a small figure walked slowly along one of the winding tracks somewhere to the east of Tennant Creek. On close examination, the figure didn’t look any different from most of his kind. He was about two feet tall and covered with short brown fur. He had a short, thick tail that dragged the ground when he walked upright and a ducklike bill where any other animal would have a nose.

The only thing that set Albert apart from any other platypus was that he was carrying an empty soft drink bottle. It was his possession of a bottle, coupled with the fact that he was hundreds of miles north of any running water, that made him different. (p. 2)

Hachette Book Group/Twelve, July 2012, hardcover $24.99 (viii + 225 pages; map by Jim McMahon), Kindle $12.99.

The novel begins with Albert the platypus staggering about in the parched desert next to the South Australia Railway tracks near Tennant Creek, somewhere north of Alice Springs. Albert has escaped from the Adelaide Zoo and is searching for … what?

The problem was that Albert had no idea where he was going, or exactly what he was looking for. The stories had been vague at best … somewhere in the desert … a place where old Australia still existed … keep going north … the Promised Land. Those descriptions had sounded good in Adelaide, but they were worthless in a desert where every direction looked the same. (p. 3)

Albert had tried to prepare for his search by stockpiling a small hoard to his food and water from his cage in Adelaide, but it had lasted only long enough to reach Tennant Creek. “Now, he was out of food, out of water, and out of plans.” (p. 4)

Expecting to die in the desert, and resolved to die as far north of Adelaide as possible, Albert stumbles into the camp of Jack the wombat. Jack has never heard of where Albert is looking for.

‘What I meant was, is this the place where things haven’t changed and Australia is like it used to be?’

The wombat thought for a long time before he answered. ‘If you mean somewhere animals run around without any clothes on while being chased by people with spears and boomerangs, the answer is no. It’s not bloody likely that you’d find old Jack in a place like that.’ (p. 12)

Albert follows Jack to Ponsby Station, a ramshackle general store in a half-played-out mine site.

Behind the bar stood a large red kangaroo wearing an apron and a dirty silk shirt with garters on the sleeves. A pair of wire-rimmed spectacles rested on his nose. Across the bar from the kangaroo were two bandicoots wearing canvas overalls. The bandicoots were so drunk they were having trouble standing up. (p. 28)

Albert is naïve but he is no softy. When he runs into anti-platypus prejudice from the marsupials, he gets ready to fight.

As both bandicoots and the kangaroo stared at Albert, he could feel the spurs on his hind legs start to extend themselves. The more they stared, the more they reminded Albert of the people at the zoo, and with each look the anger in Albert’s soul burned brighter. At the zoo there was nothing he could do, but here he might be allowed the luxury of a violent act. (p. 29)

On payday for the marsupial miners, the Ponsby Station general store becomes a place of wild revelry. Albert gets drunk, wins the other animals’ money gambling, and falls asleep. When he awakes the next morn, Jack has burned the station down. He and Albert get out of town before the other animals can form a lynch mob and come after Albert for winning all their money and for being a platypus.

Jack, feeling guilty, insists that he always causes trouble and that Albert will be better off without him. They divide their supplies, including Jack’s extra revolver, and Albert leaves.

A week ago he was, for all intents and purposes, a dead platypus. Now, the zoo was far behind him. He had made friends. He had more food and water than he had when he had left Adelaide, and he was still alive. Each of which was something he had not expected and, when taken together, equaled a small miracle. Cheered by thoughts of his survival, Albert shouldered his rucksack and began walking down the trail away from Jack and what was left of Ponsby Station. (pgs. 57-58)

Albert of Adelaide is a picaresque novel. Albert’s wanderings take him into and out of many potentially fatal situations:

Albert headed toward the light, which grew brighter and brighter until he rounded a boulder and came to its source. A large one-story wooden building stood at the edge of the boulder field, and a number of lamps hung from its side. Torches had been planted around the front of the building and large canvas signs were hung from poles on the top and at the sides.

The largest sign, lit by paraffin lamps with reflectors, was on the roof of the building. It read “WELCOME TO THE GATES OF HELL.” One sign on the side of the building read “WHISKEY AND AMMUNITION”; another read “DRY GOODS.” A smaller sign by the front door read “RELIGIOUS MEDALS, MAPS, FEMALES,” although someone had taken a paintbrush and crossed out the word FEMALES with a couple of rough strokes.

Just as Albert finished reading the signs, a large wallaby smoking a cigar walked out the front door of the building carrying a skyrocket. He wore a white tuxedo jacket and was missing half an ear. The wallaby walked over to a section of pipe that had been pounded into the ground near the front door. He put the rocket in the pipe and lit the fuse with his cigar. Then he stepped back and watched the rocket shoot upward. After the rocket exploded in the sky over the building, the wallaby turned to go back inside. As he turned, he noticed Albert standing by the boulder.

“If you’ve come for the party, it’s inside,” he said. (pgs. 65-66)

Albert of Adelaide is similar to another classic picaresque novel, Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. It’s full of rough-and-tumble small towns that Albert has to leave in a hurry after a shootout. In fact, one of the next friends and role-models he meets is Terrance James Walcott, a raccoon holdup artist and claim jumper from the California gold camps who escaped from San Francisco barely ahead of a Vigilance Committee mob.

By now the reader will have realized that Albert of Adelaide has segued from current people-inhabited Adelaide and the modern continent-spanning South Australian Railway to a 19th-century Northern Australian landscape of frontier mining camps inhabited by anthropomorphic Aussie animals; marsupials who aren’t familiar with a platypus from the Murray River and who don’t trust strangers. Albert, at first an outsider unsure whether he should abandon his search for Old Australia, becomes the leader of the odd group of animals opposing the scoundrely Bertram, the white tuxedo-wearing wallaby and Theodore, his murderously psychotic possum henchman who are tricking the citizens of Barton Springs into making them Constable, then Mayor, and finally General of the marsupial community, out to exterminate the dingo aborigines.

Albert of Adelaide is a fine anthropomorphic novel, with a rich cast of Australian animals and one raccoon immigrant. Like Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, the animals segue confusingly between being clothes-wearing imitation humans and natural animals, and being their real sizes and all human-sized. Individual clothes-wearing kangaroos hop, but a townful of them walk like humans. But the animals’ natural abilities figure in many scenes. The desert-dwelling marsupials are unfamiliar with platypuses, and on several occasions Albert’s poison spurs prove to be a powerful secret weapon. This novel should please all Furry fans.

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

Comments

I had tried to find an image of the full wraparound dust jacket, but all that I could find was the front cover. Interestingly, I kept running across illustrations of the different covers of the Australian and British editions.

http://www.allenandunwin.com/default.aspx?page=94&book=9781742379029

http://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/184668840X?tag=bookgeeks-21&camp=1406&creative=6394&l...

I had assumed at first that this was an American reprint of an Australian novel, but apparently not. “The author: Anderson, 69, a lawyer in Las Cruces, N.M., flew helicopters in the Vietnam War, worked in Pennsylvania steel mills and wrote scripts in Hollywood for several movies that were never made, ‘but they paid me anyway.’” Anderson is working on a sequel featuring T. J. Walcott, “the larcenous, whiskey-drinking raccoon.”

http://www.texasobserver.org/reviews/albert-of-adelaide-a-debut-novel-set-down-u...

Fred Patten

Five years later: Anderson has just self-published “The Famous Captain Walcott”, the first of two sequels, on Kindle. He says on GoodReads that he’s been unable to sell them to any publisher.

https://www.amazon.com/Famous-Captain-Walcott-Howard-Anderson-ebook/dp/B06Y2KGD8...

Fred Patten

Post new comment