Dispelling a misconception: Non-human animals as intelligent, cultured and moral beings

There are countless accounts and videos of animals doing amazing things and demonstrating great intelligence. However, we can never be sure if those are representative examples of animal behaviour or just once-off events. Furthermore, those are interpreted through untrained eyes and may not actually show a behaviour that people think it does. To try to avoid these issues, my goal here is to primarily rely on peer-reviewed scientific literature, ideally that which is publicly-available, but presented in a way that can be understood by all. To distinguish between scientific references and ordinary links, links to scientific sources are presented in the format [Author, year] based on academic referencing conventions.

A lingering misconception

I think that a large part of the blame for the misconception about the animal mind rests with the French philosopher René Descartes. He was of the view that animals are mindless automatons that neither think nor feel. In 1641, he wrote:

Seeing that a dog is made of flesh you perhaps think that everything which is in you also exists in the dog. But I observe no mind at all in the dog, and hence believe there is nothing to be found in a dog that resembles the things I recognize in a mind.

This sort of belief allowed Descartes to do things like throw cats out of windows and torture dogs. I also believe his views were likely crucial for the practice of vivisection. In order understand processes like breathing and blood circulation, dogs were restrained and cut open while alive, so that natural philosophers could observe their physiological processes. While that may have been very informative for medicine, it was a torturous death for the unfortunate animals.

One might hope that such beliefs are now a historical relic that has been abandoned. Unfortunately, this is not entirely the case and, in 2009, centuries after Descartes, the philosopher and theologian William Lane Craig declared:

Thus, amazingly, even though animals may experience pain, they are not aware of being in pain. God in His mercy has apparently spared animals the awareness of pain. This is a tremendous comfort to us pet owners. For even though your dog or cat may be in pain, it really isn't aware of it and so doesn't suffer as you would if you were in pain.

Given the high level of influence that he has, it's difficult to outright dismiss him as a crank.

Even organisations that work with animals may maintain this misconception, although that may be because it is convenient to do so. For example, in 2020, while supporting an ag-gag law, which is designed to prevent people exposing poor treatment of animals in agriculture, the Ontario Federation of Agriculture claimed that:

We simply do not know if animals are capable of reasoning and cognitive thought, therefore we cannot attribute human qualities of reasoning and cognitive thought on animals as the activists would like.

Together, these three examples illustrate how pervasive and long-lived is this misconception. The reality is that all three of the quoted statements are completely and utterly incorrect. The modern scientific view stands in stark contrast.

The modern scientific view

On 7 June 2012, several prominent neuroscientists and researchers from related disciplines, gathered in Cambridge, UK, for the Francis Crick Memorial Conference, honouring one of the most influential biologists. Francis Crick is probably most well known for his role in discovering the structure of DNA and for formulating the, often incorrectly stated, central dogma of molecular biology. The theme of the conference was Consciousness in Human and Non-Human Animals. At the end of the day, the participants signed the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness. This short document summarised the scientific literature on animal consciousness and declared:

The absence of a neocortex does not appear to preclude an organism from experiencing affective states. Convergent evidence indicates that non-human animals have the neuroanatomical, neurochemical, and neurophysiological substrates of conscious states along with the capacity to exhibit intentional behaviors. Consequently, the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Non-human animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess these neurological substrates.

When moving past the fairly obtuse wording, it was a statement that the scientific evidence supported, at least some, animal consciousness. Essentially, it invalidated the misconception promoted by the likes of Descartes, Craig and the Ontario Federation of Agriculture.

For several years, this was the best statement of the scientific consensus. However, on 19 April 2024, a new declaration, much clearer and more concise, was released—The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness. This declaration states:

Which animals have the capacity for conscious experience? While much uncertainty remains, some points of wide agreement have emerged.

First, there is strong scientific support for attributions of conscious experience to other mammals and to birds.

Second, the empirical evidence indicates at least a realistic possibility of conscious experience in all vertebrates (including reptiles, amphibians, and fishes) and many invertebrates (including, at minimum, cephalopod mollusks, decapod crustaceans, and insects).

Third, when there is a realistic possibility of conscious experience in an animal, it is irresponsible to ignore that possibility in decisions affecting that animal. We should consider welfare risks and use the evidence to inform our responses to these risks.

At the time of writing, the declaration had 578 signatures from those with the relevant expertise in science, philosophy or policy.

While science is not decided democratically, these declarations are a sign that the consensus of researchers is that the misconception of animals as unthinking and unfeeling beings runs contrary to the scientific evidence. Moving forward, I would like to look at some specific examples of scientific evidence of animal intelligence, language use, morality and culture as a guide for how to think about the many species with whom we share this planet.

Intelligence

There are many ways to think about intelligence and try to measure it. In this essay, I will be using intelligence as the ability to apply knowledge in different situations; more specifically, to use knowledge of how the world works to manipulate tools or cooperate in order to achieve a goal. Tool use is one of those traits which has traditionally been considered something exclusive to humans. But, over the years, this distinction has weakened and now it is just one more trait where humans are distinguished, not by kind, but by degree.

The mental territory we can claim to be “uniquely human” is shrinking at an alarming rate.

-Martha Gill, When dogs recall toys, and horses plan ahead, are animals so different from us?

Some of the best examples of tool use in non-humans come from birds. Many species, though mostly corvids, have been observed manipulating objects as tools and even solving more complex puzzles that require multiple independent pieces.

Back in 2002, there was a report about a female New Caledonian crow who bent a straight piece of wire into a hook to obtain otherwise-inaccessible food [Weir et al., 2002]. This was a special result because it suggested that the crow had an understanding of physics, could identify the need for a hook to obtain food and identified material that could be modified into a hook.

That was impressive but it was just a single object. Sixteen years later, a new study was published on compound tool construction [Bayern et al., 2018]. This time, the authors showed that the crows were able to combine dowel rods and empty syringes, neither of which were long enough individually to reach a food reward, into a longer tool which could reach the reward.

Even more recently, Goffin's cockatoos were shown to be able to use one tool (a stick) to manipulate a second tool (a ball) in order to get the ball to release a food reward [Osuna-Mascaró et al., 2022].

I said that tool use was evidence of intelligence and even said that these examples “use knowledge of how the world works.” That was not a chance statement, it was because birds do understand how the world works. One study investigated whether New Caledonian crows have an understanding of the physics of the world by subjecting them to a series of six tests about water displacement. In all trials, a food reward was out of reach of the crows unless they took specific actions. Those tests tested whether they understood 1) that a stone could displace water but not sand, 2) that objects that float will not raise the water level, 3) that hollow objects will not displace as much water as solid objects, 4) that you need to displace less water in narrow tubes, 5) that higher water levels can be reached more easily and 6) whether they could infer which tubes were connected by a hidden pipe. The results showed that, except for 4 and 6, the crows completed the tests with a performance above chance, indicating that they had a reasonably accurate mental model of how the world functions [Jelbert et al., 2014].

While there are many studies on birds, we should not get the wrong idea and think that other animals do not use tools or solve puzzles. There is a widely-used experimental design, the cooperative pulling paradigm, which tests cooperation in animals using tools. This test uses a mobile platform with a food reward that is out of reach of the animals. That platform can be moved forward to receive the reward by pulling on two ends of a rope. However, the rope is not fixed to the platform, so if an animal only pulls one end, the rope will slip free and the platform will not move. The reward can only be reached if two animals cooperate and pull both ends of the rope together. This requires intelligence to not only understand the test mechanism but also to cooperate with another individual to achieve the same goal.

This cooperative pulling paradigm has been studied in several species across the evolutionary tree and seen success in diverse species like keas [Heaney et al., 2017] and elephants [Plotnik et al., 2011]. We will focus on work done at the Wolf Science Center, a short distance from Vienna.

The scientists at the Wolf Science Center saw that wolves and dogs were both able to cooperate with a human partner [Range et al., 2019] and that wolves were able to cooperate, very successfully, with each other [Marshall-Pescini et al., 2017]. In contrast, dog pairs never managed to cooperate and solve the puzzle. What is also very cool, and emphasises their understanding of the puzzle, is that the wolves were successful in a delayed version of the test. In the delayed version, one wolf is released first, there's a 10-second delay and then the second wolf is released. Not only does the first wolf know to wait and not pull the string alone but you can also see how much slower it approaches the apparatus when it knows it can't be done yet.

The tools that animals can learn to use can be completely different from anything they would encounter in the wild. One of the best examples is rats learning to drive tiny cars [Crawford et al., 2020]. Not only can they learn to drive cars but they enjoy it too! Rats are probably not an animal that many people look at as being intelligent, but they are. That they can learn to drive shows how adaptable they are and why it's important to provide animals mental stimulation in their housing.

It's not only lab animals that have learned to use tools; this occurs in the wild and new examples continue to be found. Examples reported this year include sulphur-crested cockatoos in Sydney using public drinking fountains as their preferred source of water [Klump et al., 2025], chimpanzees in Uganda treating wounds with medicinal plants [Freymann et al., 2025] and orcas using pieces of kelp to massage one another [Weiss et al., 2025]. Together, all this shows that animals are intelligent enough to understand how the world works and are able to use that information, along with tools, in order to accomplish their goals.

Language

Communication is widespread among animals and can occur through vocalisations, body postures, scents and other actions. While it is possible to communicate with other animals, humans have long desired to talk to them through language, as evidenced in stories like Arthur C. Clarke's Dolphin Island. There is nothing wrong with this desire unless it leads us to disregard non-language communication and falsely think there is no way for animals to communicate their feelings. I would hope that most people with a pet will quickly learn that other animals can communicate when they want attention or food or to be left alone. Anyone who is caring for an animal should learn a bit about how it communicates. Interestingly, sometimes other animals, like cats, put in the effort to meet us half-way. Adult cats seldom meow at one another; meowing seems to be specifically directed to humans because we are otherwise not very good at understanding their preferred communication. Be more like a cat and make the effort to communicate better.

Can animals learn to understand or use language—a more structured form of communication with distinct words and grammar which is necessary for communicating complex ideas. There have even been some well-known, albeit controversial, cases of animals learning to use human language such as Koko the gorilla and Alex the African grey parrot. Some scientists even worry that the differences between how we study human and animal communication mean that we might be overlooking very important information [Cartmill, 2023], particularly the emphasis on an immediate response with animal communication.

Unless reading this paper led to a predictable response in readers (e.g., angrily throwing it across the room or immediately designing a new study), standard methods in animal communication would conclude that the paper had no meaning. Methods for determining meaning in animal signals are not good at detecting communicative acts with delayed reactions, acts that impact internal states rather than external behavior, or acts that are embedded within ongoing interactions and are difficult to isolate.

Behavioural and neurological studies have both supported the idea that dogs can understand human language. Chaser the border collie, previously covered on Flayrah, is one of the best examples. She learned the names of over 1000 individual toys, was able to infer the names of unknown toys (as seen in the NOVA video with Neil deGrasse Tyson) and understood common nouns as categories [Pilley & Reid, 2011]. In addition, Chaser could distinguish between prepositional object, verb, and direct object, i.e. she knew the difference between “take X to Y” versus “take Y to X”, and she formed mental images of the objects, allowing her to complete the commands even when the objects were not visible (or even in the room) at the time the command was given [Pilley, 2013]. This ability of dogs to mentally visualise an object based on hearing language was later confirmed by measuring the electrical activity in the brain [Boros et al., 2024] and was already described in a previous Flayrah article.

While dogs can understand human language, other animals may have their own form of language. By analysing a dataset of thousands of vocalisations during conflicts of Egyptian fruit bats, along with information about which bats were making the sounds and the context in which they were made, scientists found that the cries contained a huge amount of information. Using machine learning to classify the sounds allowed them to accurately predict the identity of the bat emitting the sound, what the conflict was about and the identity of the other individual in the conflict [Prat et al., 2016]. Since they could identify which bat was being addressed, it suggested that bats might have names for each other. While bats having names might sound strange, we've seen the same thing in dolphins. Dolphins have what is known as a “signature whistle” and this essentially acts as a name, allowing dolphins to address a specific individual [King & Janik, 2013]. (Dolphins have also been reported to attempt to mimic human speech [Ridgway et al., 2012].)

While not all of that is a clear sign of animals having their own language, it does show that animal communication is more complex than we often believe and that many animals can learn to understand language to a certain degree. With wider adoption of tools like FluentPet talking buttons and reports that orangutan vocalisations contain patterns which resemble features of human language [Lameira et al., 2024], more is sure to be discovered soon.

Morality

Some people might think that one of the differences between humans and other animals is that humans know the difference between right and wrong, whereas animals merely follow their base instincts. In the biblical story, Adam and Eve were forced to leave Eden after eating the fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. More naturalistic philosophies identify human morality as an evolved property and expect that other animals will share aspects of our morality.

This certainly seems to be the case for Capuchin monkeys. This video comes from the famed primatologist Frans de Waal who gave a TED talk titled Moral behavior in animals. (If you do watch it, you will also see the cooperative pulling paradigm come up again.) In this experiment, two monkeys were kept side-by-side and given a task of returning a small rock to a researcher. When they completed the task, they were rewarded. The reward was either a piece of cucumber, which the monkeys are perfectly happy with, or a grape, which the monkeys much prefer. What they found was that monkeys were happy to perform the task for cucumber but would get upset if they saw the other monkey getting rewarded with grapes. This shows that monkeys have some sense of fairness and are upset by a situation where they are given a lesser reward for the same task [Brosnan & de Waal, 2003].

With the monkeys, we saw that other animals have a sense of fairness but, in that video, the individual was also losing out on a better reward, so it could have been a selfish reaction. What about morality when the animal has nothing to gain and, perhaps, even something to lose?

To see examples of that, we can turn to research done in rats. Rats display empathy and will take actions to relieve the distress of a second rat. This has been tested by having one free rat in a cage and one rat which is trapped in a smaller restrainer. The free rat, once it learns to open the restrainer, will quickly open it to free a trapped cagemate but will open an empty restrainer less often and take longer to do so. Not only that but, if there was also a restrainer with chocolate in it, the free rat would eat less chocolate than when it was alone and share the rest with its trapped cagemate [Bartal et al., 2011].

Finally, we return to work from the Wolf Science Center where they investigated whether dogs or wolves would perform an action that had no benefit to them but would benefit a partner. Specifically, the subjects had the option to press a touch screen with two symbols. One would reward a partner in an adjacent enclosure and the other would provide no reward. The subject who pressed the touch screen would get nothing in both cases. When they ran the experiment, they found that wolves press the button to give a partner a reward more often than when there is no partner [Dale et al., 2019]. Dogs did not show any preference for the buttons. This was taken as evidence that the cooperative nature of wolf packs makes them more willing to perform actions that help their pack mates while dogs do not have this sort of cooperative ability. (Recall also that dogs failed to cooperate with one another in the cooperative pulling paradigm.) Wolves did not press the button to help wolves that were from a different pack, showing that there is a social dynamic to this.

In summary, multiple species show some form of moral behaviour. That includes notions of fairness, empathy, a willingness to sacrifice for others and a desire to help other members of their social group with no direct benefit to themselves.

Culture

We all recognise that animals have behaviours but do they have cultures like humans do? Culture is not something that is instinctual, it is something which is taught and passed on through generations via social learning. It is something which is unique to a specific group... but not unique to humans.

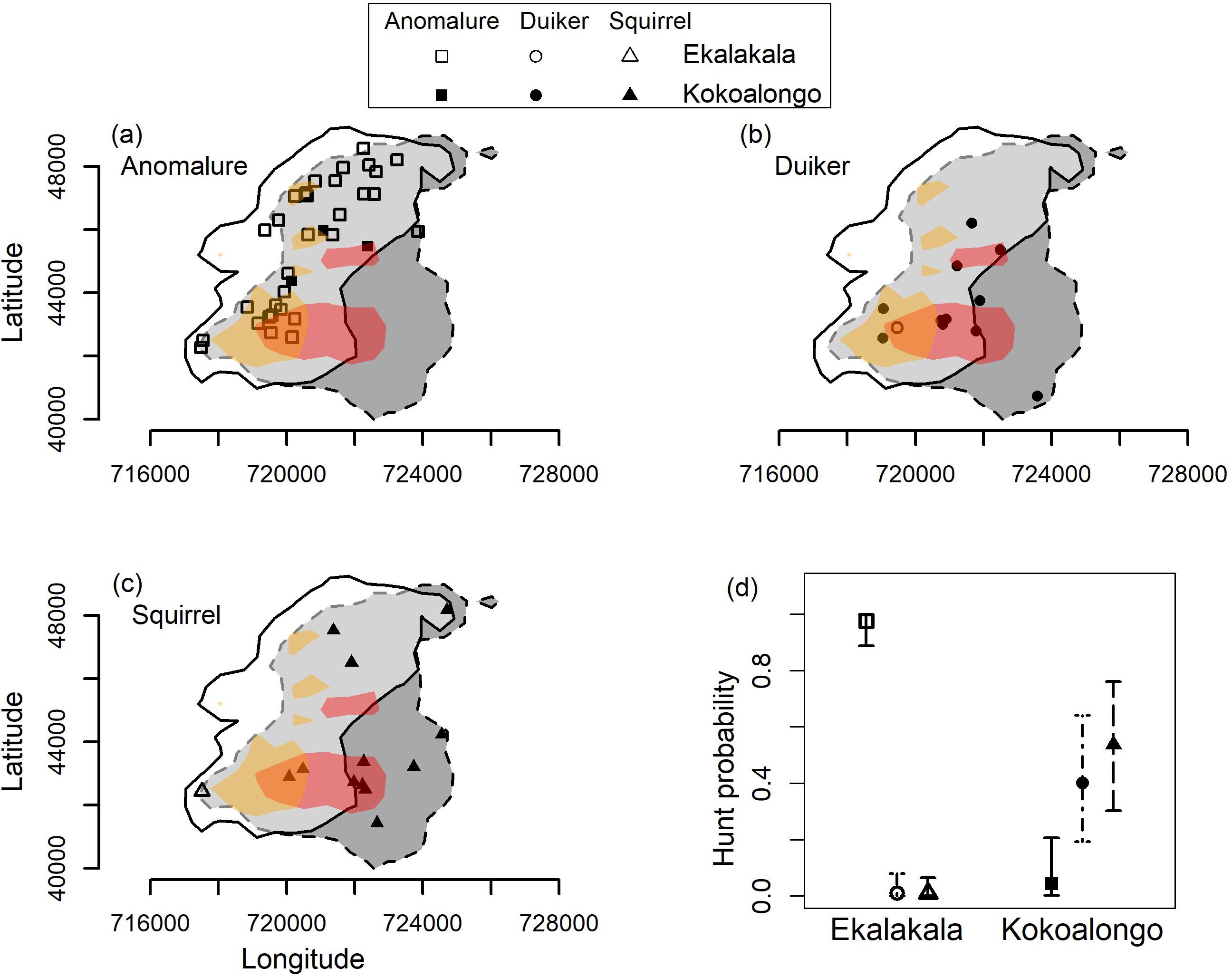

There's always a risk that what we observe as cultural differences may actually be driven by differences in the environment, for example how much or what kind of prey is available. That's what makes this next study of our close relatives, bonobos, in the Democratic Republic of Congo so interesting. In the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve, there are two groups of bonobos: Ekalakala and Kokoalongo. The territories of these two groups largely overlaps, meaning that both groups experience the same environment and prey abundances, factors which could otherwise explain differences between the groups. There's even mating between the groups, so they have limited genetic differences. However, there is a marked difference in their hunting preferences with the Ekalakala group preferring to hunt anomalure (a type of flying squirrel) and the Kokoalongo group hunting either duiker (a small antelope) or Congo rope squirrels. The most likely explanation for the differences between these groups is cultural differences that likely persist as a way to reduce conflict over prey when the groups' ranges overlap and they are in regular contact [Surbeck et al., 2020].

Once again, a trait which was thought to be exclusively human—culture—has been found to exist in other animal species as well. While it may not have developed to the extent that it has with us, it is only a difference of degree, not of kind.

Conclusion

To sum up, we can say that:

- Animals can think and are probably more intelligent than you think they are.

- Several animals may be able to understand, and even use, human language, while some other animals may have their own version of language.

- Some animals may have a sense of morality.

- Some animals may possess cultures.

Furthermore, I believe this is just the beginning. The examples we've seen are not restricted to our closest relatives nor are they specific to any particular group of animals. We see these examples coming from all across the tree of life; monkeys, crows, rats, dogs, dolphins. While individual species may lack some traits, it seems appropriate that our default assumption is that other animals possess these traits unless there is a reason to doubt that. The idea that animals could think or feel was once dismissed as anthropomorphism; mainstream science now accepts that humans are not unique in these respects.

You might note that many of the studies I cite here have only been published in the last 10 years or so. This is not only because those are the easiest to find, it's also because few people were asking these questions until recently. In several of these studies, the animal subjects are even named. This is something very new. When Jane Goodall began her studies of chimpanzees in the 1960s, several scientists objected to her naming the chimps. Now naming animals is commonplace and even described as "vital."

As research continues and more scientists look for examples of high levels of animal intelligence, tool use, language, morality and culture, I believe they will find it. There is sufficient evidence to show that the misconception about animals that has been with us for centuries is no longer tenable. It is our duty to share that evidence until the misconception has been dispelled from every mind.

Further reading

The Emotional Lives Of Animals: A Leading Scientist Explores Animal Joy, Sorrow, and Empathy ― and Why They Matter, Mark Bekoff, New World Library, 2024

Kindred Spirits: One Animal Family, Anne Benvenuti, University of Georgia Press, 2021

A Plea for the Animals: The Moral, Philosophical, and Evolutionary Imperative to Treat All Beings with Compassion, Matthieu Ricard, Shambhala, 2017

Why Animals Talk: The New Science of Animal Communication, Arik Kershenbaum, Viking, 2024

This article was adapted from two presentations of the same name. The original version was prepared in March 2021 and presented at FURSAverance, an online South African furry event held to keep people's spirits up during covid times. It was later updated and presented in March 2025 at Gdakon, a Polish furry convention.

About the author

Rakuen Growlithe — read stories — contact (login required)a scientist and Growlithe, interested in science, writing, pokemon and gaming

I'm a South African fur, originally from Cape Town, who spends most of his time in Europe. I'm interested in all sorts of things, particularly science, furry and some naughtier things too!

Comments

I think animals do have a certain intelligence and maybe a "culture" for lack of a better word, but each ones is different, maybe fundamentally. Part of my reasoning for why we can be Otherkin and it's not just some fantasy is because we have common ancestors with other species, and you can even get these odd combos like canine and feline because they share a common ancestor. But we have a reptile aspect, too, and have an ancestor that was very shrew-like.

One time during a bout of sleep paralysis, I'm nearly convinced I experienced that shrew-like state, because all I knew was something was about to seal my eternal doom, and I had no idea of who I was, or what "I" is, but I felt like this tiny little critter with huge, black eyes. It is like a proto-self, though, and I think that's what some animals have.

Take an octopus, though. Apparently, they have brains like teenagers, except their whole body is like a brain, and also they live in the ocean, which sounds not unlike whales and dolphins. Keko, aka Free Willy is a really sad story IRL because the whale wasn't able to integrate back into whale society.

Still no single-celled organism kin, though. I guess this merits further study!

Okay, this is not the discussion we are supposed to be having, and I don't even really believe in Otherkin stuff myself, but it does make sense that more "kin" would have connections to big, stronger, more complex, and more "charismatic" animals than simpler, smaller less powerful animals, even if those kind of animals are more numerous. An apex predator is outnumbered by other species many times over, and yet it still dominates the ecosystem in a way other species don't. (Or at least we imagine so; and this is a thought experiment, so what we imagine does count.) So, maybe there are a lot of people with sponge spirit animals out there or even cyano-bacteria, but those are literally sedentary creatures who don't do anything, so how could you even tell if that was your spirit. Meanwhile, sure, there are a lot less tiger spirits out there, but they are noticeable, because they're fucking tigers, so if you got a tiger spirit, you notice it (alternatively, more powerful animal spirits are more able to attach themselves to people, or both). So that's why you get a lot of big, tough mammals, and even some "weaker", smaller animals like, say, a rabbit, have strong symbolic associations for humanity, and so gain strength that way ... while a lot of simpler invertebrates and stuff are neither powerful, nor do they take up a lot of humanity's mindspace, even if they do take up a lot of literal space (any religion will tell you "biological" success and "spiritual" success are not usually the same thing).

Anyway, I actually shared that with a Portal of Evil spinoff and they actually responded ... really positively. To be clear though, I don't actually believe in any of this, and this is just a thought experiment.

... Ayight, LOL, you do you and shit. At least I believe the reptile part, the rodent part, the parts that have some similarities to whatever animals and of course the hybrid-ape part are all equally real and don't leave it at "I'm a wolf because look, I wear a mask and sit on all 4s!" Not that I do either thing.

Not reading all that, but no matter how much you rationalize it Rakuen, no, animals can't consent and you can't fuck them.

Literally thought about tweeting "annoying anon going to comment about zoos in Rakuen's article by the end of the night" and then link it at you, but I had a moment of faith in humanity ther, thanks for fucking that in the ass, anon.

When you die, hell will suck worse. Have a nice weekend.

You know your friend so well! Look at you, slumming with pedos and feigning halfway aware about it.

Why don't you write 16729024 words about how not mad you are so nobody will read them.

Visiting this site, no matter how long a break you take, is like playing the first few Smackdown games. You'll still see the same 5 moves and cutscenes over and over again and watched simulated fight wondering when it's your turn to pretend to be cool.

Animals can't consent and you can't fuck them, pass it on.

I will always appreciate how this article has not a single word relating to this topic yet you people enjoy projecting whenever possible

Smarter people than you can read between the lines based on the long history of a known creep.

Oh bullshit.

The only thing I could see the person doing close is simply having an opinion based off following logical thinking involving sensitive topics. Guess what though? That's not evil, and fictional victimless characters that don't even look like children are not evil either in case thats why you are using that cringe username.

I don't see any proud predator behavior but you extremist reactionists certainly can't help it to the point of focusing on this person over sort of "Peter Singer" style opinions rather than focusing against proud actual predators preying on real children.

Yeah I've seen a history of Rakuen but all Igeneral generally see is a person being more of a fan of evidence based research and somewhat logic over many topics. That being said I'm not saying I've seen it all and I don't think I agree with everything but even if I see an non-attacking lawful opinion I don't agree with, it's that person's right to have it. He's one of those people that tries to be rational on some topics like how I do the same on some sensitive topics myself, and all I see so far is you acting like a typical reactionist pathetic person over it. Go join the police and stop real predators from harming children assuming you REALLY care.

I feel like pretty much the only furry in the fucking fandom who will admit they don't like cub/ageplay stuff because they find it gross, they're allowed to feel that way, it doesn't have to be logical, but also knows full well it's an awful lot easier to feel like a hero in your own mind about cartoons than it is to protect actual kids. And on the more cynical side of things, it gets harder and harder all the time to be the coolest kind of keyboard warrior. It takes increasing effort to look like you do a lot when you do so little. Cheating is harder, basically.

"smarter people can read between the lines" Sweetheart, that's also what people say to justify their theories on how lizards wrote the declaration of independence. You gotta give actual, specific examples if you like... wanna make a point instead of just sounding like a paranoid weirdo.

sidenote, why tf is the automatically assigned "Anon" name flagged as unavailable? that's potentially the only thing here even stupider then this entire fucking comment section.

I'm not sure, but I think since dronon started using an "Anon" account to post the Newsbytes Archives, the system has started counting it as a "registered user". This has only recently come up, though, so I don't think he actively registered the Anon account, and "Anon" is not in the Contributor's List, but it probably has something to do with it.

No, someone actually registered the name half a year ago and used it to post a comment. Since they don't seem to have otherwise used it I removed the account and assigned the comment to their email address instead. Amusingly this issue is fifteen years old and hasn't been fixed in Drupal core. But a patch exists; I've applied it.

Oh, when I post the Newsbytes, I remove my name from the author field, and the system automatically assigns it that username instead. I figured if I was posting these once a month, it's almost always a group effort, and I didn't want to inflate my posting stats.

Sorry that I've been pretty distant for the last month, it's stress and family drama - I'm hoping to get back into the swing of things after mid-October, once Canadian Thanksgiving is over with.

Few people who come here have much of an ability to converse like normal people even when given every opportunity. Here's a good rule of thumb, give 'em 1, maybe 2 chances, and if you get even a whiff of the sense that somebody's trying to make you a character in the fiction they need to live out in the last existing non-paywalled comments section left, just deny them that. No one's *entitled* to your time or a reply, are they? But trust me, they think they are! Every time you just don't engage and keep doing your thing, chances are, they're stamping the ground in frustration with their lil' footies goin' like Roadrunner LOL

They're like wrestlers, or perhaps I'm more inspired by those whereas they're inspired by influencers, but nonetheless, they're living for the reaction from the crowd, even as it dwindles in size by the year. Whereas the *new* netizen lives to react as little as possible, engage as little as possible, to be an almost non-netizen, on the web, but not of the web.

Not trying to start a religious debate with 2cross but, although I greatly entertain his Abrahamic beliefs, even within my semblance of such belief my Native American instinct kicks in and says they will not make hell worse when they die, because they will neither go there, or wait it out in purgatory, or return in the resurrection. They're not salvageable unless perhaps something outside their or our control happens upon them to give them enough of a life that a soul can inhabit that body. Does one weep for dust?

Mr. N-Bone, do not defend the anonymous jerks ever again.

Do you understand me?

How mad you are about being seen slumming with pedos.

Are you like, putting it back on me all these months later?! XD Which anonymous asshole did I defend, though? Like, I pretty much just spew off the top of my head after a puff, go off to do something else and forget I was ever in la-la land here so it might not even be hypocrisy as much as being a stoned dumbass who doesn't pay attention.

Well, that actually explains a lot. I'm being serious here, but, for one thing, the paranoia. Maybe get with your provider and perhaps try a new varietal or strain, because, yeah, you get paranoid. Other than that, you do post like you're high a lot, so, yes, that makes sense. Sometimes its kind of hard to parse what side you're on, especially if I'm already kind of peeved. Sorry for the misunderstanding ... this time. That being said, I do have notes!

You did join that anon in attacking the Good Furry Award guy, like, just last week; that wasn't cool. Yes, that guy is kind of a goober, but right now he's our goober, and he does have a point; he started the award to try and highlight positivity in the fandom, and in reaction a lot of people have gone out of their way to use that as an excuse to dig for and highlight negativity even harder, which is frankly kind of gross.

Also, you need to let the Calbeck thing go, especially since that's in a obituary comment section; you post high, you've got to expect that people might not appreciate your contributions to what is essentially a memorial post. But honestly, as swipes go, Calbeck's swipe at you was basically playful; you kind of got really paranoid really fast, I am serious about that, but if you're getting a lot of one stars right now, well, you kind of are posting bad there, so that's actually what they're for. Also, Calbeck is pointedly ignoring you now, and not replying, so it's over already, really. It's just you at this point. You should let that one go, I think.

Okay, less sarcastic have a good weekend for you!

Alright, now let's hear why the rise in a lot more 1-star posts is somehow a fluke, or doesn't matter, etc. About the Good Furry Awards, I'm pretty sure I wasn't high when I wrote that. It's a way I've felt about the fandom for a long time, it's reminiscent of the local festivals or committees in all those old (and dying) towns that take things way too seriously. And Calbeck, I took his initial comment in good faith, didn't reply, but he had to, *had to* go have another go and I *anticipated* that! And then I thought a bit more about it and said, it's pretty much always like this when someone comes out of the blue at me like that and tries to grandstand over something like that. Why? Because I seen it anytime someone dies. You just learn patterns as you get old as fuck - and he's even older, still trying to do this. When you try to sue for ownership of a "Battltech" game system thing because you wrote a fanfic about it you're on some Chris Chan shit, and it's like if you came up at me swinging your fists and fell face first in a pit of the mud you created decades ago. Yeah I'm gonna laugh!

I mean rise in more than 1 star posts. To avoid confusion and shit. Everyone's 1-starring everybody like they'll win a contest at the end so, no, it's never a fluke if me or anybody gets 1-starred - and yes, all your posts are golden and none deserve it, I know you believe that so I won't challenge it LOL

BTW, Rakuen, congratulations on triple digits! And what an article to hit it on; your animal science articles are one of your strengths, and are a good fit for your academic background. Thank you for contributing!

Also like to add your free speech opinions are looking much better right now ... for admittedly the worst reasons imaginable (seriously, it's getting hard to access porn on the Internet!), so also thanks for not gloating!

Thank you! I had been planning to write this for months. I decided to turn it into an article when I was getting ready for Gdakon. I thought it would take 2-3 weeks to write up after the convention because I already had done all the research. In the end it took months because I kept doing other things. But when I learned it would be 100, I decided this should really be the one. My other ideas are not as cool for a milestone.

Yes, there's a series of very troubling attacks on free speech and privacy right now. And it's coming from places that are supposed to safeguard people's rights and liberties. In the US, it's still fuelled by religion and now exacerbated by a complete idiot in charge. In the EU and UK, I assume it's a mix of paternalism and paranoia resulting in a need to control and monitor everything. They don't think can be responsible for themselves. Depressing times.

"If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind."

~John Stuart Mill~

If only your supposed concern applied to actual issues, instead of the "ayckshyually its ephebephilia" faux-libertarian pose.

"So and so politician did a witch hunt" doesn't make it imperative to get in bed with actual pedos that PedoBunny was made to harbor. Your loli collection is not a righteous manifesto. Diddling minors is not resistance. Getting your hard drive checked would be a normal society noticing what you stand for.

And being anti-pedophilia/anti-zoophilia is not a brave moral stance, it's baaically the default (next you'll come out as anti-murder), so it does not justify bullying a guy online, especially if you're going to be a boring fuck while doing it.

I mostly agree with your stance, here (because, once again, it's the bare minimum default), but other than the occasional deranged comment, Rakuen doesn't actually do what you're accusing him of, except, I don't know, he may "like" a piece of cub art every now and then on ... I think he's a SoFurry partisan, actually? I think he has a "18+" Twitter account, and I'm

sure I don't want to see what he's up to there, so I don't fucking go there.

But the truth is this isn't about the evil, Rakuen does, this about the evil you do. Because you know anonymously stalking a guy across the Internet is a shitty thing to do, but you like doing it, so you picked a victim you can say is "worse" than you, so you're in the clear, right? Sorry, buddy, it doesn't work like that. You're still a shitty little guy.

And I better point this out now, because you're stupid in addition to evil, but this is not a defense of Rakuen. It is an attack on you. Yes, you make me angry. Shitty, stupid evil posters make me angry.

But I could forgive all that if if you just weren't so fucking boring on top of it. Just, I don't know, post better!

Well, have another nice weekend, and I accidentally spam marked Rakuen's comment, it should be back eventually. Sorry about that.

Not only everything you said, but I'm going to give the biggest, fattest, most grotesque example of the guy who makes not liking pedos his entire identity. Alex Rosen AKA Chet Goldstein AKA a bunch of other names. His entire thing is to roll up on someone he RP'd as a minor with, sting them with the dox, have a convo about how and why the suspect's into minors - none of his fans find it odd that he enjoys this so much, and dropping all the keywords predators would use when it's the biggest red flag - and then they usually never even get charged. Sure, most of us have a visceral hatred for the monster-predator archetype, whether imagined or a real one in the news, but it's a very, very small percent of the population that will take so many risks and break norms or even laws to force a pervert to talk about it with them, so... I just see shades of that in a lot of comments sections or social media threads sometimes. I have a love-hate relationship with a lot of things but it really disturbs me when anyone can have even the slightest love side to a hateful relationship like that.

"Basically the default" yet you manage to blow even this credibility non-test, which shouldn't have to be discussed, until your pedo-pals come wallowing in the mud where the site ownership put it in the first place.

Swerving and dodging and declaring yourself cool doesn't wipe off that stain, but do post 163289 more words about how mad you aren't. It's funny how internet privacy only matters when it's your pedo-pals concern, but not when they get criticized. :)

I do not consider a single person here a friend and am not really the kind of person that can be made friends with easily, because I have about 163289 inches of titanium in the wall between me and every person on the internet, who is not already a friend. You'll adopt the same practice out of necessity. You'll evolve. Out of sheer pressure. Or simply lose whatever outlets you have to the digital rot! In a way, I welcome enshittification and the botscape. No more of predators, no more apologists, but most of all, no more comments, no more unqualified "critiques" from wouldbe philosophers... no more you.

:-)

Yeah, that's why

... Why what?! I don't think I put a question in there, LOL Unless you mean "you choose to be a loner" or something like that.

Are you high too? Is everyone in this comment section high but me?

Edit: Believe it not, not high when I wrote about animal spirit charisma. I know, right?

"Is everyone in this comment section high but me?" Man, I have some bad news about what internet you've been on this whole time and didn't know LOL

He's Inkbunny staff now.

We brought on a few community moderators early this year, yes. Like many, he's been a member since 2010.

Possibly helped that SoFurry is… transitioning now, somewhat controversially (and has been since July 10 - I worry this may become a SheezyArt situation). Work on the new site (by TerraBAS) has been ongoing since ~2022.

Well, congrats to him either way.

Heh, so apparently the default Anon name can't be used anymore. Saying it belonged to a registered user. Maybe a new code to except that could be made?

Now to add some tax:

I actually do find this topic interesting. I remembered hearing that many cats can use similar emotion responses like humans or close. The moral thing is interesting though but not quite sure if such will ever be as complicated as some humans use but I'm open to more good research about it.

Also I do think though a lot of people do already know some animals are different in terms of intellgence by the way.

This article reminds me of an old Reader's Digest I read as a kid, Intelligence in Animals. It was structured really similarly. This is cool because it's using knowledge and research that is much more recent. I'll have to check out the books you suggested - I already had The Emotional Lives of Animals on my read list (maybe because I'd seen you mention it somewhere?).

Have you ever been in a book club?

My family had like two or three decades of Reader's Digests which I reread several times. We stopped subscribing sometime in the early 2000s, I think. Maybe it was like 2010. The quality went down sharply. It was printed on worse paper and like half the length that it used to be.

Anyway, I recommended the revised version of The Emotional Lives of Animals but I've only read the original. There's good stuff there though I wasn't entirely a fan of the way it was written. I hope the revised version fixes those problems. Still very much worth looking through. I'm not sure if I mentioned it anywhere before.

I have not been in a book club. I don't read nearly as much as I did as a kid. Or, at least, I don't read books as much. I've only finished one book this year! Shameful.

"If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind."

~John Stuart Mill~

The way you were talking about it, I assumed it was deader than disco a long time ago. But it seems like it's still going "strong." It seems at some point, the font changed and had some stupid shit done to it with some little red triangle for the apostrophe in Reader's and another triangle snipped off the inside of the D in Digest to force it to vaguely resemble a speech balloon. Oh wow, it looks so "digital age" now, by which I mean dumb and ugly as shit. Why, just why?! You have a perfectly decent, even iconic logo known the world over, and you ruin it! Utterly ruin it!

Okay I'll get off my graphic design font-nazi soapbox now, geeze.

Rakuen wrote: "I don't read books as much. I've only finished one book this year! Shameful."

When i was younger I could complete a book read faster (sometimes completely reading a novel in one day).

In recent years, most of the books i finish reading are graphic novels.

Maybe some of your local libraries have some graphic novels that you would like to read. (and if they don't have something, please ask them to get it)

Examples:

a) 'Lower Your Sights: A Benefit Anthology for Ukraine"

b) (on a lighter note) any Spider-Ham book (Marvel)

c) some of the stuff published by Vertigo (DC imprint: which has' relaunched https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vertigo_Comics#2024_relaunch )

d1) 'Animosity' series (published by Aftershock): animals of the world start speaking human language, started taking revenge, and chaos ensues. The main 'Animosity' series follows human girl (Jesse) and pet dog (Sandor) traveling across USA to find Jesse's older brother. (I'm only partway through 'Animosity' main series.)

d2) There are also the spin-offs: 'Animosity: Evolution' and 'Animosity: The Rise'.

I've been doing some gaming at least. I have the recent graphic novel adaptation of Watership Down!

"If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind."

~John Stuart Mill~

the post: cool article about animal intelligence

90% of the comments for some fucking reason: "fun fact I don't fuck kids"

like... okay? good thing, just... why are you randomly bringing that up? Like idk maybe i'm missing something cause i'm new here but like... randomly exclaiming that you're not a pedo when nobody asked is just gonna make em think you are.

Your lazy shitpost is wrong on at least 1 level (keeping my reply short, because I have too many other things to do):

1) you (“AnotherAnon”) wrote: “for some f***ing reason”

Other people in the comments are responding to

1a) frequent anon’s use of display name that starts with “Pedo” and end with “Watch” (I’m abbreviating their display name to “anonPRW”) … ie. any of anonPRW’s posts is accompanied by display NAME that is a VAGUE accusation of pedo-whatever.

1b) some of anonPRW’s comments (on this webpage) have vague/generic/paranoid accusation of pedo-whatever.

I took it as an admittedly late in the game callout of PedoWatch guy that also admittedly exaggerated how frequently they posted, rather than a callout of Flayrah in general, as the comment is complimentary to the article up top. They also seem to be more directly calling them out in another comment, and I find it unlikely we got two random anons in this particular thread on this particular day.

Post new comment